- Surname:

- Faltlhauser

- First name:

- Valentin

- Era:

- 20th century

- Field of expertise:

- Psychiatry

- Place of birth:

- Wiesenfelden

- * 28.11.1876

- † 08.01.1961

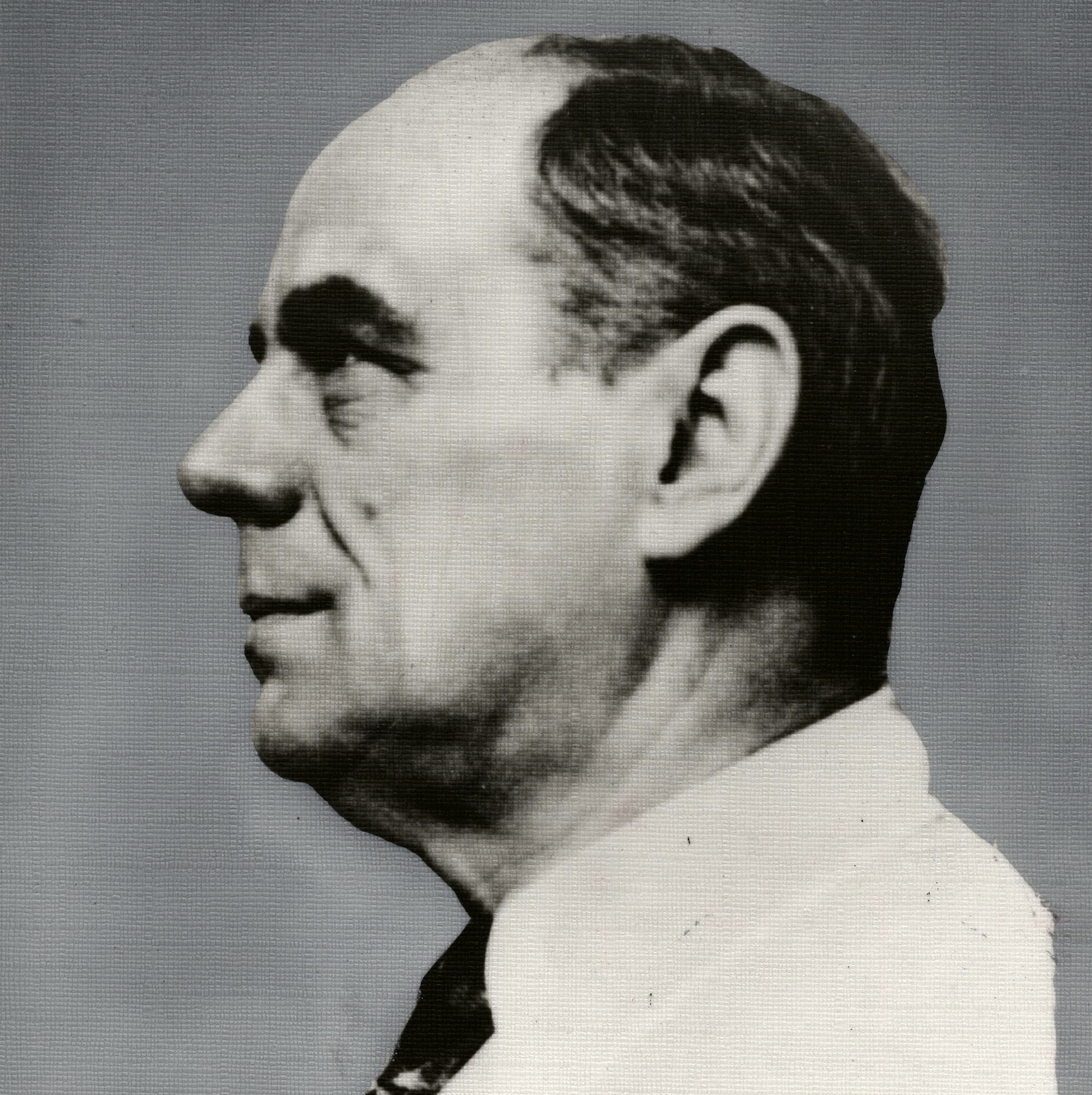

Faltlhauser, Valentin

German psychiatrist, involved in patient killings during the Nazi era.

Valentin Faltlhauser (1876–1961) was born on 28 November 1876 in Wiesenfelden in rural Lower Bavaria. His father’s position as an estate manager enabled him to attend higher education, first in Metten and then in Amberg. He initially began studying law in Munich but switched to medicine after just one semester. Having moved to Erlangen in 1899 to continue his studies there (Pötzl 2012: 385 f.), he soon developed an interest in psychiatry and neurology. Particularly influential were his two of his university teachers: the internist Adolf Strümpell (1853–1925) and Gustav Specht (1860–1940), the latter of whom also supervised Faltlhauser’s doctoral thesis Casuistischer Beitrag zur Chorea Huntingdon’s[A Casuistic Contribution on Huntingdon’s Disease], completed in 1906. From 1903, Faltlhauser first worked as a stand-in junior physician at the district asylum in Erlangen. He was promoted to the rank of a medical officer during his military service in 1905 and served as a regimental physician in the infantry during World War 1. Back in Erlangen after the war, he treated so-called “war neuroses”.

Work as a reform psychiatrist

After the war, the director of the Erlangen asylum, Gustav Kolb (1870–1938), implemented the concept of “open care” at his facility with the aim of systematically complementing “closed inpatient care” with outpatient aftercare (cf. Ley 2002). Faltlhauser, by then a senior physician, became a prominent advocate of “open care” provided by clinic-based facilities. He was granted a leave of absence from his duties as a clinic doctor in 1922 and used this time to promote “open care” in numerous publications (i.a., in collaboration with his mentor, Gustav Kolb, and his colleague Hans Roemer (1878–1947)). Faltlhauser was appointed deputy director in Erlangen and, on 1 November 1929, became the director of the asylum Kaufbeuren-Irsee in southern Bavaria. There he also introduced the system of “open care” despite the strained public budgets and the increasing underfunding of psychiatric facilities in the wake of the world economic crisis.

In the early 1930s, Faltlhauser still rejected the use of eugenic concepts in population policy – this, however, changed after the Nazis had come to power in January 1933. According to Pötzl (2012: 389), his career in the years thereafter was characterized by three elements: “Firstly, the establishment of a modern psychiatry, secondly, the focus on racial hygiene and forced sterilization, and thirdly, the associated identification with National Socialism” (translated from German). As was the case with other perpetrators from the psychiatric community, Faltlhauser’s craving for professional recognition probably played a decisive role in his turning to Nazi racial hygiene (cf. Schmuhl 2013). Michael von Cranach (2010: 84) identifies the following reasons for Faltlhauser’s involvement: “The Nazi idea of exterminating those who are unproductive, preemptive obedience in an extremely hierarchical environment and the associated elimination and transfer of conscience to the highest-ranking authorities, careerism, financial incentives, the desire to be part of the innermost circle of ‘reformers’ – these are only a few aspects that may have contributed to the fabric of conditions underlying his path to perpetration” (translated from German).

Activities during the Nazi era

In Kaufbeuren, Faltlhauser set up a hereditary and genealogical database (“Erb- und Sippenkartei”), founded a local branch of the German Society for Racial Hygiene, and, from the mid-1930s, openly advocated forced sterilization. He was in contact with the Nazi’s leading expert on racial hygiene, Ernst Rüdin (1874–1952), worked for the Nazi Party Office of Racial Policy and as an assessor at the Hereditary Health Court in Kempten (Harms 2010: 408). From 15 August 1940, Faltlhauser officially acted as an “Action T4 expert”: he selected patients for killing and compiled the lists for their deportation to the killing centers Grafeneck (Baden-Württemberg) and Hartheim near Linz (Austria). When public discontent and, in particular, protest by the Churches led to the official discontinuation of the “Action T4” operation in 1941, Faltlhauser became a driving force for the next phase of Nazi “euthanasia” – the murder of inmates in the asylums themselves. He developed the low-calorie “E-diet” (“euthanasia diet”), which led to the death of an estimated 11,000 patients in Bavaria alone (cf. Klee 2014: 415 f.). The Kaufbeuren asylum also established so-called “special wards” where patients were killed by medication overdosing; moreover, they were used for human experiments. From 5 December 1941, the institution was home to a “Kinderfachabteilung”, a specialized children’s section (Schmidt et al. 2012: 295), for which Faltlhauser repeatedly requested the assignment of “euthanasia-experienced” staff (von Cranach 2010: 84 ff.). A total of 221 children and adolescents were killed in this department. In this context, Faltlhauser is also responsible for the death of fourteen-year-old Ernst Lossa (1929–1944), who died there on 9 August 1944 from a lethal injection of morphine-scopolamine (Schmidt, Kuhlmann, von Cranach 2012: 292; Kolling 2017).

Prosecution

Faltlhauser was arrested by the US Forces shortly after the end of the war in May 1945. According von Cranach (2010: 85), he cited three arguments to justify his deeds in court: Firstly, his “sense of duty” as a civil servant, who had learned to obey laws and orders unconditionally and had thus been convinced to act in accordance with the dictates of humanity. Secondly, his “compassion” out of which he had always acted with the intention of relieving people from suffering and that he had always considered himself a conscientious doctor. Finally, he referred to a “consensus in society, as euthanasia had not been invented by the Nazis but had been an issue in health policy for decades” (ibid.; translated from German). On 30 July 1949, the regional court in Augsburg sentenced Faltlhauser to three years in prison for inciting and aiding and abetting manslaughter in at least 300 cases (cf. sources 1,2,3), a sentence that Ernst Klee (1986a: 198) described as “extremely lenient” (cf. Rüter & de Mildt 2012: 175–188, court case No. 162, LG Augsburg, court ruling No. 490730). Moreover, it was never carried out: after Faltlhauser had repeatedly been deemed unfit for imprisonment, he was pardoned by the Bavarian Minister of Justice in 1954 (Harms 2010: 408). Valentin Faltlhauser died seven years later, on 8 January 1961, at a retirement home in Munich at the age of 84 (Kolling 2017).

Influenced by his mentor, Gustav Kolb, and by colleagues like Hans Roemer, Faltlhauser realized the reformist potential of “open care” as an outpatient complement to the German asylum system and thus as a cost-cutting form of modernization. His turning to racial hygiene after 1933 and his active collaboration with the Nazi regime highlight the then-prevailing desire to modernize psychiatry, the ideological offers of Nazi population policy, and the associated career opportunities for physicians during the Nazi era. Against this background, Faltlhausers statements in court regarding his active involvement in the killing of patients are to be read as the typical self-protective assertions of a perpetrator.

Commemoration of the victims

The historical evaluation of Faltlhauser’s activities in Kaufbeuren owes, above all, to Michael von Cranach (born 1941), the long-standing medical director of what is now the district hospital Kaufbeuren. He campaigned for the commemoration of the patient killings in Kaufbeuren and throughout southern Germany in numerous publications. Today, there are several places of remembrance of the crimes committed during the Nazi era, both at the district hospital and at Irsee Monastery, a former branch of the hospital.

In 2008, Robert Domes published the fictionalized biographical novel Nebel im August. Die Lebensgeschichte des Ernst Lossa [Fog in August. The Life Story of Ernst Lossa]. The movie adaptation of the book, directed by Kai Wessel, appeared in 2016. In the role of a character modeled on Faltlhauser, actor Sebastian Koch paints the picture of a career-minded, conscienceless, and convinced perpetrator.

Sources

(1) Landgericht Frankfurt, Urteil wegen Euthanasie gegen Pauline Kneissler u.a., 28. Januar 1948; Staatsarchiv Sigmaringen Wü 29/3 T 1 Nr. 1759/03/09. Permalink:http://www.landesarchiv-bw.de/plink/?f=6-904690-2.

(2) Oberstaatsanwalt beim Landgericht Frankfurt, Schreiben vom 18. 11. 1948; Staatsarchiv Sigmaringen Wü 29/3 T 1 Nr. 1759/03/09. Permalink:http://www.landesarchiv-bw.de/plink/?f=6-904690-31.

(3) Staatsarchiv Augsburg: Best. Staatsanwaltschaft Augsburg KS 1/ 49, Band I-VIII.

Literature

Braunschweig, S. (2013): Zwischen Aufklärung und Betreuung. Berufsbildung und Arbeitsalltag der Psychiatriepflege am Beispiel der Basler Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Friedmatt, 1886–1960. Zürich: Chronos.

Cranach, M. v. (2010): Mitwissen und Kooperation. Die Haltung der Anstaltspsychiatrie. In: M. Rotzoll (ed.): Die nationalsozialistische “Euthanasie”-Aktion “T4” und ihre Opfer. Geschichte und ethische Konsequenzen für die Gegenwart. Paderborn: Schönigh, pp. 83–90.

Cranach, M. v., H. L. Siemen (1999, eds.): Psychiatrie im Nationalsozialismus. Die Bayerischen Heil- und Pflegeanstalten zwischen 1933 und 1945. Munich: Oldenbourg.

Faltlhauser, V. (1906). Casuistischer Beitrag zur Chorea Huntington’s. Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Medicine at the Faculty of Medicine of Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen.

Faltlhauser, V. (1923): Geisteskrankenpflege. Ein Lehr- und Handbuch zum Unterricht und Selbstunterricht für Irrenpfleger und zur Vorbereitung auf die Pflegerprüfung. Halle: Marhold.

Falthauser, V. (1927): Die Fürsorgeorgane. In: H. Roemer, G. Kolb, V. Falthauser (eds.): Die offene Fürsorge in der Psychiatrie und ihren Grenzgebieten. Berlin: Springer, pp. 199–228.

Faltlhauser, V. (1931): Offene Psychiatrische Fürsorge von der Anstalt aus in die Großstadt. In: O. Bumke, G. Kolb, H. Roemer, E. Kahn (eds.): Handwörterbuch der psychischen Hygiene und der psychiatrischen Fürsorge. Berlin, Leipzig: De Gruyter, pp. 123–127.

Faltlhauser, V. (1934): Erbpflege und Rassenpflege. Halle: Marhold.

Faltlhauser, V. (1939): Kurzer Leitfaden der allgemeinen Krankenpflege. Halle: Marhold.

Heuvelmann, M. (2013): Wer in einer Gottesferne lebt, ist im Stande, jeden Kranken wegzuräumen. Geistliche Quellen zu den NS-Krankenmorden in der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Irsee. Irsee: Grizeto.

Klee, E. (1986, ed.): Dokumente zur Euthanasie. Frankfurt on the Main: Fischer.

Klee, E. (1986a): Was sie taten, Was sie wurden. Ärzte, Juristen und andere Beteiligte am Kranken- und Judenmord. Frankfurt on the Main: Fischer.

Klee, E. (2001): Deutsche Medizin im Dritten Reich. Karrieren vor und nach 1945. Frankfurt on the Main: Fischer.

Klee, E. (2003): Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945? Frankfurt on the Main: Fischer.

Klee, E. (2014): Euthanasie im Dritten Reich. Die Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens. Vollständig überarbeitete Neuausgabe. Frankfurt on the Main: Fischer.

Kolling, H. (2017): Faltlhauser, Valentin. In: H. Kolling (ed.): Biographisches Lexikon zur Pflegegeschichte. “Who was Who in Nursing History.” Vol. 7. Berlin/Wiesbaden: hps-media, pp. 75–80.

Kolling, H. (2017a): Heichele, Paul. In: H. Kolling (ed.): Biographisches Lexikon zur Pflegegeschichte. “Who was Who in Nursing History.”Vol. 7. Berlin/Wiesbaden: hps-media, pp. 109–114.

Ley, A. (2002): Die Verminderung der Hausbesuche erklärt sich durch die anderweitige Inanspruchnahme der Fürsorgeärzte. Zu den Auswirkungen des Sterilisationsgesetzes auf die Offene Fürsorge für Geisteskranke. In: S. Stöckel, U. Walter (eds.): Prävention im 20. Jahrhundert. Weinheim: Juventa, pp. 122–135.

Mitscherlich, A., F. Mielke (1962, eds.): Medizin ohne Menschlichkeit. Dokumente des Nürnberger Ärzteprozesses. Frankfurt on the Main: Fischer.

Mader, E, T. (1982): Das erzwungene Sterben von Patienten der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren-Irsee zwischen 1940 und 1945. Nach Dokumenten und Berichten von Augenzeugen. Blöcktach: Verlag an der Säge.

Pötzl, U. (2012): Dr. Valentin Faltlhauser. Reformpsychiatrie, Erbbiologie und Lebensvernichtung. In: Cranach, M. v., H. L. Siemen (eds.): Psychiatrie im Nationalsozialismus. Die Bayerischen Heil- und Pflegeanstalten zwischen 1933 und 1945. Munich: Oldenbourg, pp. 385–403.

Raueiser, S., Sellner, B. (2009, eds.): Man stolpert mit dem Kopf und mit dem Herzen. Zum Gedenken an die Opfer der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren/Irsee. Irsee: Grizeto.

Roemer, H., G. Kolb, V. Falthauser (eds.): Die offene Fürsorge in der Psychiatrie und ihren Grenzgebieten. Berlin: Springer.

Römer, G. (1986): Die grauen Busse in Schwaben. Wie das Dritte Reich mit Geisteskranken und Schwangeren umging. Berichte, Dokumente, Zahlen und Bilder. Augsburg: Wißner.

Rüter, C. F.; de Mildt, D.W. (2012): Justiz und NS-Verbrechen, Vol. V, Court Proceedings No 148–190 (1949), here No 162: Faltlhauser, Valentin. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, pp. 175–188.

Schmidt, M., Kuhlmann, R., M. v. Cranach (2012): Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren. In: M. v. Cranach; L. Siemen (eds.): Psychiatrie im Nationalsozialismus. Die bayerischen Heil- und Pflegeanstalten zwischen 1933 und 1945. Munich: Oldenbourg, pp. 265–325.

Schmuhl, H.-W. (2013): Psychiatrie und Politik. Die Gesellschaft Deutscher Neurologen und Psychiater im Nationalsozialismus. In: C. Wolters, C. Beyer, B. Lohff (eds.): Abweichung und Normalität. Psychiatrie in Deutschland vom Kaiserreich bis zur Deutschen Einheit. Bielefeld: transcript, pp. 137–157.

Thom, A.; G. Ivanovič (1989, eds.): Medizin unterm Hakenkreuz. Berlin: Volk und Gesundheit.

Gereon Frederick Breuer

photo: Copyright, Historisches Archiv des Bezirkskrankenhaus Kaufbeuren.

Referencing format

Gereon F. Breuer (2020):

Faltlhauser, Valentin.

In: Biographisches Archiv der Psychiatrie.

URL:

biapsy.de/index.php/en/2-uncategorised/289-faltlhauser-valentin

(retrieved on:08.09.2025)