- Surname:

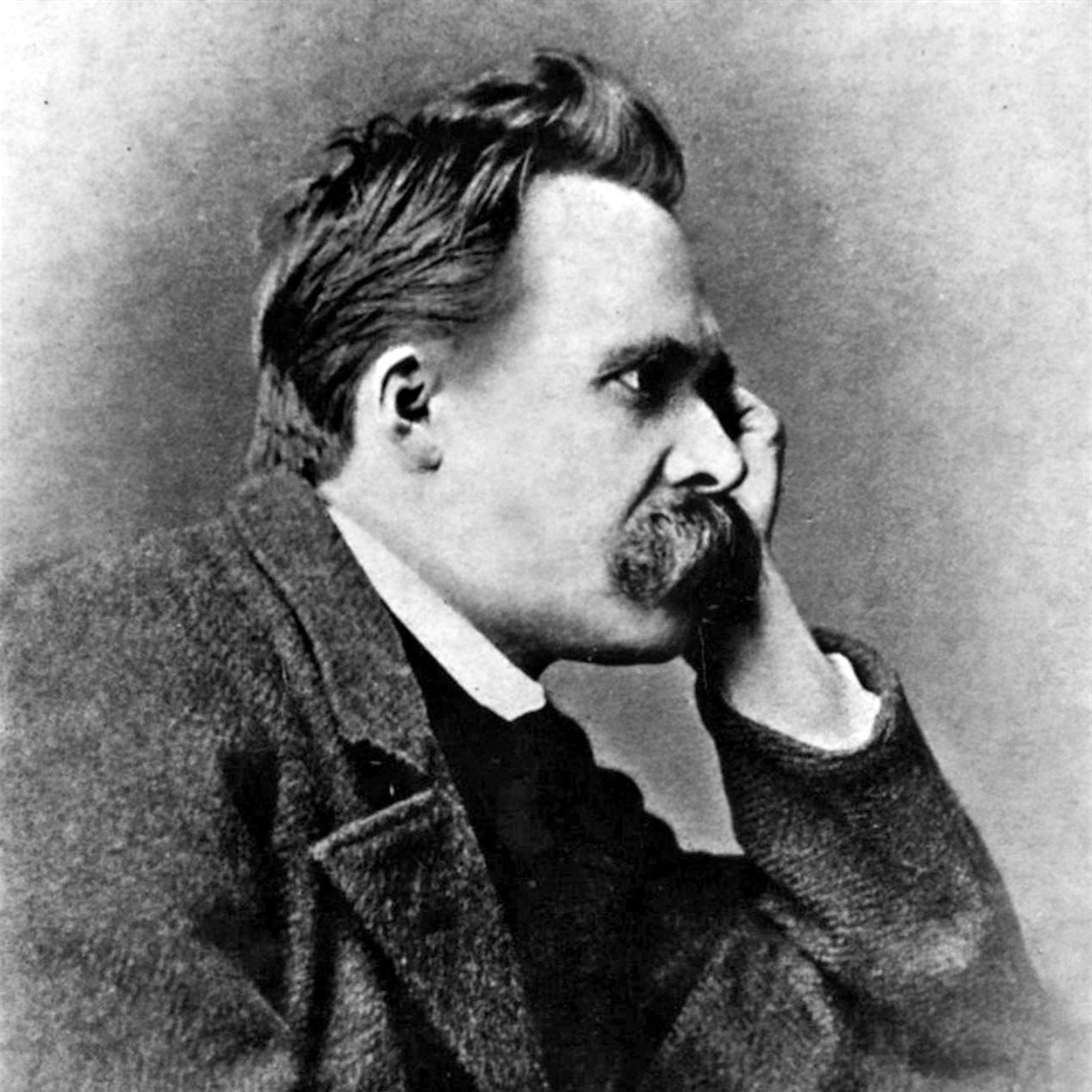

- Nietzsche

- First name:

- Friedrich Wilhelm

- Era:

- 19th century

- Field of expertise:

- Philosophy

- Place of birth:

- Röcken (DEU)

- * 15.10.1844

- † 25.08.1900

Nietzsche, Friedrich

German classical philologist and philosopher.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was born in Röcken, in the then Prussian Province of Saxony. He ranks as one of the most important philosophers of the late 19th century, and the profound influence of his thinking is felt still today. He began his studies in classical philology in 1864, first in Bonn and then in Leipzig. Only four years later, at age 24, he was appointed professor of classical philology at the University of Basel, Switzerland. Nietzsche had suffered from various health problems since childhood, inter alia, migraine, depressions, insomnia, and myopia. At the end of the 1880s, however, he also developed serious psychological symptoms including signs of progressive dementia, which gave rise to a wide range of diagnostic speculations after his death.

Diagnoses and progression

There has never been an all-conclusive explanation for Nietzsche’s symptoms. Supposed causes include syphilis (Möbius), intoxication by chloral hydrate (Langbehn, Cohn), mental exhaustion (Paasch, Masur, Lackner), schizophrenia (Muthmann, Lenz, Cormann), epilepsy (Lampl, Bernoulli), presenile dementia (Grosse), mania (Nordau), and depression (Schacht). In 1889, Nietzsche’s own doctors diagnosed “progressive paralysis” as a result of neurosyphilis, an untreatable condition in those days. This diagnosis – long considered the most viable explanation – has recently again been contested (cf. Tenyi 2012), for instance, by Sax (2003; brain tumor), Hemelsoet et al. (2008; CADASIL syndrome), or Koszka (2009; MELAS syndrome).

Nietzsche himself consulted countless doctors. Moving to a warmer climate, to places like Sorrento or the Riviera, brought only temporary relief. The daily use of choral hydrate, a sedative and sleep-inducing drug, also had merely palliative effects. In autumn 1888, after long and productive periods during which he wrote his key works, Nietzsche began sending so-called “Wahnsinnsbriefe” (madness letters) – short and cryptic messages suffused with ideas of grandeur – which deeply worried the addressees, for instance, historian Jacob Burckhardt (cf. Volz 1990: 254 ff.; 371 ff.). On January 3, 1889, while in Turin, Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown: He allegedly threw his arms around the neck of a flogged horse in order to protect it and then collapsed in the street. His close friend Franz Overbeck took him to Friedmatt Sanatorium in Basel where Ludwig Wille diagnosed progressive paralysis with psychotic states as the final stage of untreated tertiary syphilis. Seven weeks later, his mother had him transferred to Grossherzogliche Sächsische Landes-Irren-Heilanstalt, a mental clinic in Jena under the direction of Otto Binswanger. There the diagnosis “dementia paralytica” was confirmed. In March 1890, with Nietzsche’s condition deteriorating, his mother removed him from the clinic to care for him at her home in Naumburg. After the mother’s death in 1897, his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche took the ailing philosopher to Weimar where she cared for him until he died at age 56 on August 25, 1900. Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche – who also took some liberty with the material when assuming control of her brother’s writings and their publication – always denied that he had syphilis.

The diagnostic debates evolving around Nietzsche’s illness clearly illustrate the methodological problems inherent in traditional pathography and retroactive diagnostics, as they often remain highly speculative. A reliable test for syphilis was developed only in 1906 by August von Wassermann, six years after Nietzsche’s death.

Literature

Gschwend, G. (2000): Pathogramm von Nietzsche aus neurologischer Sicht. In: Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 81, (1), pp. 45–48.

Hemelsoet, D., K. Hemelsoet, D. Devreese (2008): The neurological illness of Friedrich Nietzsche. In: Acta Neurologica Belgica 108, (1), pp. 9–16.

Khazaee, K. M. (2008): The case of Nietzsche’s madness. In: Existenz - International Journal in Philosophy, Religion, Politics, and the Arts 3, (3), pp. 40–48.

Koszka , C. (2009): Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900): a classical case of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome?In: Journal of Medical Biography 17, pp. 161–164.

Möbius, P. J. (1902): Ueber das Pathologische bei Nietzsche. Wiesbaden: Bergmann.

Podach, E. (1961): Nietzsches Werke des Zusammenbruchs. Heidelberg 1961.

Poltrum, M. (2012): Nietzsche als Diagnostiker, Patient und Psychotherapeut. Philosophie als Arzneimittel im Dienste des wachsenden und kämpfenden Lebens. In: K. Brücher, M. Poltrum (Hg.): Psychiatrische Diagnostik. Berlin: Parodos, S. 136-164.

Sax, L. (2003): What was the cause of Nietzsche’s dementia? In: Journal of Medical Biography 11,pp. 47–54.

Schain, R (2001): The legend of Nietzsche’s syphilis.Westport: Greenwood Press.

Tényi, T. (2012): The madness of Dionysos -- six hypotheses on the illness of Nietzsche. In: Psychiatria Hungaria 27, (6), pp. 420–425.

Volz, P. D. (1990): Nietzsche im Labyrinth seiner Krankheit. Eine medizinisch-biographische Untersuchung. Würzburg: Königshausen + Neumann.

Burkhart Brückner, Robin Pape

Photo: Gustav-Adolf Schultze (d. 1897) / Source: Wikimedia / [public domain].

Referencing format

Burkhart Brückner, Robin Pape (2015):

Nietzsche, Friedrich.

In: Biographisches Archiv der Psychiatrie.

URL:

biapsy.de/index.php/en/9-biographien-a-z/71-nietzsche-friedrich-wilhelm-e

(retrieved on:02.07.2025)