- Surname:

- Carcasse

- First name:

- James

- Era:

- before 1700

- Field of expertise:

- Other

Carcasse, James

(or Carkesse). English teacher and school principal, inmate of Bethlem Hospital.

James Carcasse (around 1636 – after 1690) was most likely born and raised in England, though little is known about his life, and the spelling of his name varies. A graduate of Westminster School, London, he enrolled at Christ Church College, Oxford, in 1652 and received his Bachelor of Arts in 1656/57 (Bloxam 1863: 176; cf. Natali 2016: 46 f.). In 1663, he was principal of the prestigious Magdalen College School at Oxford. Carcasse became a member of the Royal Society in 1664 and worked as a clerk to the Royal Navy from 1666 onwards. He was acquainted with Samuel Pepys, the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty, who repeatedly mentioned him in his famous diary. In two entries from 1667, for instance, Pepys described him as being desperate and a schemer (388; 555; see digital version). Carcasse became principal of Chelmsford Free School in Essex in 1676. In 1678, he was forced into treatment at Finsbury Madhouse, followed by six months at Bethlem Hospital, London, from where he was discharged on 29 November 1678 (“recovered to his mind and reason”; cf. O’Donoghue 1915: 219, Minutes of the Hospital's Court of Governors; see digital version). Carcasse seems to have returned to his previous position as school principal in Chelmsford, at least the records indicate that he still held this position in 1690.

Poets are mad

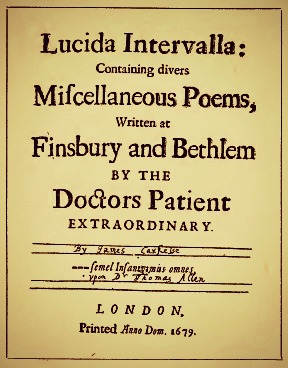

James Carcasse became known for his collection of 53 poems titled Lucida Intervalla: Containing Divers Miscellaneous Poems, Written at Finsbury and Bethlem by the Doctors Patient Extraordinary, published in 1679. This 67-page work is one of the most important sources on everyday life in two early modern asylums from a patient’s perspective. Many of the poems are dedicated to his visitors who supplied him with food, clothing, a chair, oranges and pencils. Carcasse described the purgatives administered, the doctors’ astro-medical hypotheses and the chains used in isolation cells (1679/1979: 32). He denied being insane, and when his doctor, Thomas Allen, who was considered progressive at that time, refused to discharge him unless he gave up writing, he declared the doctor to be insane himself:

The Riddle

Doctor, this Pusling Riddle pray explain;

Others, your Physick cures, but I complain

It works with me the clean contrary way,

And makes me Poet, who are Mad they say.

The truth on’t is, my Brains well fixt condition

Apollo better knows, than his Physitian:

‘Tis Quacks disease, not mine, my Poetry

By the blind Moon-Calf, took for Lunacy.

James Carcasse (1679/1979: 32) firmly called for “civilised” treatment. His work is thus not only the first personal account ever published by an inmate of a “madhouse” (as a specific type of institution), but also represents an early example of the sub-genre of protest against the conditions of treatment in madhouses, asylums and psychiatric hospitals.

Literature

Arnold, C. (2008): London and Its Mad. London: Simon & Schuster.

Bloxam, J. R. (1863): A Register of the Presidents, Fellows, Demies, Instructors in Grammar and Music, Chaplains, Clerks, Choristers, and Other Members of St. Mary Magdalen College in the University of Oxford from the Foundation of the College to the Present Time. Vol. III, The Instructors in Grammar. Oxford: Henry & Parker.

Brückner, B. (2007): Delirium und Wahn – Geschichte, Selbstzeugnisse und Theorien von der Antike bis 1900. Vol. 1: Vom Altertum bis zur Aufklärung. (Schriften zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Vol. XXII). Hürtgenwald: Pressler.

Calvi, J. (2013): “Is’t Lunacy to call a spade, a spade?” James Carkesse and the Forgotten Language of Madness. In: R. Falconer, D. Renevey (eds.): Medieval and Early Modern Literature, Science and Medicine. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 143-156.

Carkesse, J. (1679): Lucida Intervalla: Containing Divers Miscellaneous Poems, Written at Finsbury and Bethlem by the Doctors Patient Extraordinary. Los Angeles: The Augustan Reprint Society 1979.

Ingram, A. (1998): Patterns of Madness in the Eighteenth Century. A Reader. Liverpool: University Press.

MacLennan, G. (1992): Lucid Interval. Subjective Writing and Madness in History. Rutherford, Madison, Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Natali, I. (2016): 'Remov'd from human eyes' – Madness and Poetry 1676-1774. Firenze: Firenze University Press.

Natali, I. (2013): James Carkesse and the Lucidity of Madness: A “Minor Poet” in Seventeenth-century Bedlam. In: International Journal of the Humanities 9, (5), pp. 285-298.

O'Donoghue, E.G. (1915): The Story of Bethlehem Hospital from its Foundation in 1247. New York: Button.

Pepys, S. (1667): The Diary of Samuel Pepys. A New and Complete Transcription. Edited by R. Latham and W. Matthews. Vol. 8. London: Bell & Hyman 1974.

Porter, R. (1987): A Social History of Madness: The World Through the Eyes of the Insane. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Burkhart Brückner

Referencing format

Burkhart Brückner (2015):

Carcasse, James.

In: Biographisches Archiv der Psychiatrie.

URL:

biapsy.de/index.php/en/9-biographien-a-z/86-carcasse-james-e

(retrieved on:04.07.2025)